Tomorrow we get to have the ultimate say about our preferred federal parliamentary representatives as each of us get one vote in the House of Representatives and one vote in the Senate.

Polling suggests that this election could be close. Newspoll out on Monday had the Coalition ahead 51 to 49%, Essential poll out on Wednesday had Labor on 51% and so did the Fairax Ipsos poll out last night. But if you dig further into the reports from these polls, there is about 30% of respondents who state that they could change their mind, or that they still haven’t decided. And a straw poll in the CEFA office shows about the same.

You might be wondering what the Constitution says about how we are represented in the Parliament, so this week we explore parliamentary representation, elections and vote counting.

Voting in the House of Representatives

A fundamental principle which underlies our Constitution is the idea of representative government, thus the House of Representatives is the people’s house. Section 24 of the Constitution outlines this principle:

Section 24 Constitution of House of Representatives

The House of Representatives shall be composed of members directly chosen by the people of the Commonwealth…

Further into section 24 is the “one vote, one value” principle. This means that the number of MP’s per state shall be in proportion to the numbers of people in that state, with the minimum number for each original state at five. So for the 2016 election we will elect the number of MP’s in each state in accordance to population of each state. This will be 47 MP’s in NSW, 37 in Victoria, 30 in Queensland, 16 in Western Australia, 11 in South Australia and the minimum five in Tasmania. And due to Section 122 of the Constitution, each of the two internal Territories, the NT and the ACT have just two Members. The Parliament decides the level of representation in the territories:

Section 122 Government of territories

The Parliament may…allow the representation of such territory in either House of the Parliament to the extent and on the terms which it thinks fit.

At the end of 2015 the population of the ACT was 393,000, the NT 244, 000 and Tasmania (who get five seats) 517,400.

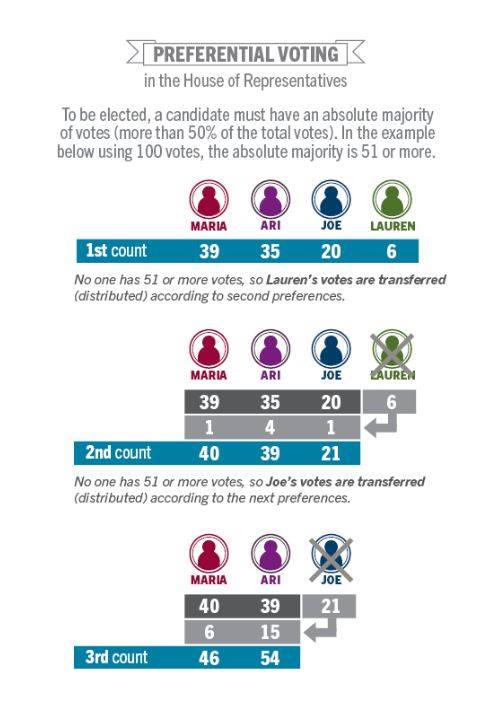

We’ll each get two ballot papers tomorrow. The small green one is for the House of Representatives. The person who you give the number 1 to is your chosen candidate. You then need to number all the other boxes in order of your preference, because of our preferential voting system. To win the seat a candidate must obtain more than 50% of the total votes and this 50% can be won on preferences if it is not alreadt achieved as primary vote in the first round count. About the House: Australian Parliament House of Representatives published a picture a couple of days ago showing how the votes are counted in the House:

Voting in the Senate

The Senate is the States House and each of the Original States in Australia must have the same number of Senators. At the moment there are 12 Senators in each State and since this is a double dissolution election all 12 seats are up for grabs. There are also two Senators for each of the Internal Territories (in accordance with section 122).

The people that wrote our Constitution left it up to the Parliament to decide on the method of choosing our Senators, as long as they are directly chosen by the people and that the method is the same for all states. This is stipulated over a couple of sections:

Section 7 The Senate

The Senate shall be composed of Senators for each State, directly chosen by the people of the State…

Section 9 Method of election of senators

The Parliament of the Commonwealth may make laws prescribing the method of choosing Senators, but so that the method shall be uniform for all the States. Subject to any such law, the Parliament of each State may make laws prescribing the method of choosing the senators for that State.

Our Senate voting method is more complex than the House and has changed since the last election. Each of us still only get one vote in the Senate, but how we make our preferences has changed. This is outlined in the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918.

To submit a valid vote at this election you will need to number a minimum of six boxes above the line or a minimum of 12 boxes below the line. Although there are savings provisions in case people make a mistake and only vote 1 above the line or six below the line. This means that if you make this mistake at this election your vote will still be counted.

If you only vote for 12 independent or micro party candidates below the line, your vote may exhaust. Meaning your one Senate vote won’t be used to elect a candidate. We’ve been chatting to people who are happy for their vote to exhaust, rather than give it to a major party. But by having your vote exhaust, it means you don’t actually have a say in the make-up of our Senate. If you keep numbering boxes past 12 (for other independents and micro parties), there is a higher chance that your vote will stick with one of them (you can number all the boxes above the line or all the boxes below the line). But the new election method allows you to make the choice for your vote to exhaust.

How are the Senate votes counted?

The first thing to think about with Senate vote counting is the quota system. As this is a double dissolution each candidate must receive 7.69% of the vote to gain a seat. The way this is worked out is 100% of votes/12 seats + 1 runner up, so it’s 100/13 (in a normal half Senate election it is 100/7).

To start the Senate count all of the first preference votes are counted and allocated. At this point several people will be elected, and some will have more than the required 7.69% of the vote. These extra votes above the quota are called a surplus.

The AEC state that the next thing that happens in the count is that surpluses are transferred.

So if you vote above the line, the first candidate below that line under the party you’ve numbered is the candidate you’ve given your first preference to. If a lot of other people vote the same way, that candidate will have many more votes than the required 7.69% quota. These surplus votes are then given a transfer value.

What the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) (or their computer software) does is re-examine every ballot paper that gives the first preference to this elected candidate and look at the second preferences. The surpluses are then transferred in the same percentage as all of the second preferences in that group of ballot papers. The AEC have a handy example of how the transfer values are calculated:

Candidate A gains 1 000 000 votes. If the required quota was 600 000 the surplus would be 400 000.

The transfer value for candidate A's votes would be:

400 000 / 1 000 000 = 0.4

Candidate A's ballot papers (1 000 000) are then re-examined in order to determine the number of votes for second choice candidates.

If candidate A's ballot papers gave 900 000 second preferences to candidate B, then candidate B would receive 360 000 votes (900 000 multiplied by the transfer value of 0.4). These votes would be added to the votes candidate B received in the first count.

If, on receipt of candidate A’s surplus votes, candidate B has then reached the quota, they are elected. If candidate B has any surplus votes, a transfer value would be calculated and votes would be transferred in the same way.

The confusing thing about our voting method is that we tend to think we are giving our vote to a party, rather than a candidate. However, if you vote above the line, the candidate you are giving your vote to, is the first person listed under the line. Your second preference is the second person in that list under the line and so on until all of the people in that list have a preference from you. Then we move onto the party you have given your number 2 to, and the first candidates listed below the line in this list receives your next preference and then the candidate under them and so on.

If you vote below the line, it is much clearer who you are actually giving your preferences to. They are in the order that you make them.

Once the surpluses have been distributed, the next thing that happens in the Senate count is that unsuccessful candidates begin to be excluded. To use NSW for example, there is 151 candidates. After the first preference votes are counted and the surpluses are transferred, the candidate who came 151st in the vote will be excluded. The ballot papers that gave them a 1 will be distributed to the remaining candidates based on the preferences of those ballot papers. If any of the remaining candidates obtain a quota from these preferences they are elected and any surpluses are transferred. Then the overall count is looked at again, the person who is next last is excluded and the distribution of their ballot papers allocated out according to the preferences that voters have made. This goes on until we have elected 12 candidates in the States and two in the Territories.

Because we now have a partial preferential voting system, it means that during the counting process, there will likely be some votes that exhaust. If none of your preferences gain a seat in the Senate, it means that your vote was one that exhausted. And because of these exhausted votes the last one or two Senate Candidates in each State may be elected without a full 7.69% quota.

How many exhausted votes will we have? How many invalid votes will we have? If we put those two figures together at what percentage is our democracy compromised? If 85% of people choose 100% of the Senators? 75%? 50%?

Lisa Hill Professor of Politics, University of Adelaide has written a piece in the Conversation this week explaining why we have a compulsory voting system. She states that:

Governments are more representative and therefore more democratic when everyone votes.

And:

Compulsory voting regimes have lower levels of corruption….They also have higher levels of satisfaction with the way democracy is working than do voluntary systems. In compulsory voting regimes – where just about everybody votes – government attention and spending is more evenly distributed across social classes.

This might be a controversial question, but is deliberately letting your vote exhaust the same as not voting? Let us know what you think.

Photo attributed to the AEC